Trevor Davis

Trevor, can you tell me a little bit about yourself?

I’m a freelance graphic designer. I’m from South Florida, but I’ve been in New York for four years now. I also teach design through a nonprofit organization called the Abron Arts Center, which works with minority students.

You went to school for design, right?

Yeah, I went to Savannah College of Art and Design. I went for animation. And then after that just went into graphic design.

What were your experiences at SCAD? What the race situation was like there? I’ve talked to a lot of people from RISD and it seems to be hit or miss. And I feel SCAD is the other major design school in the country.

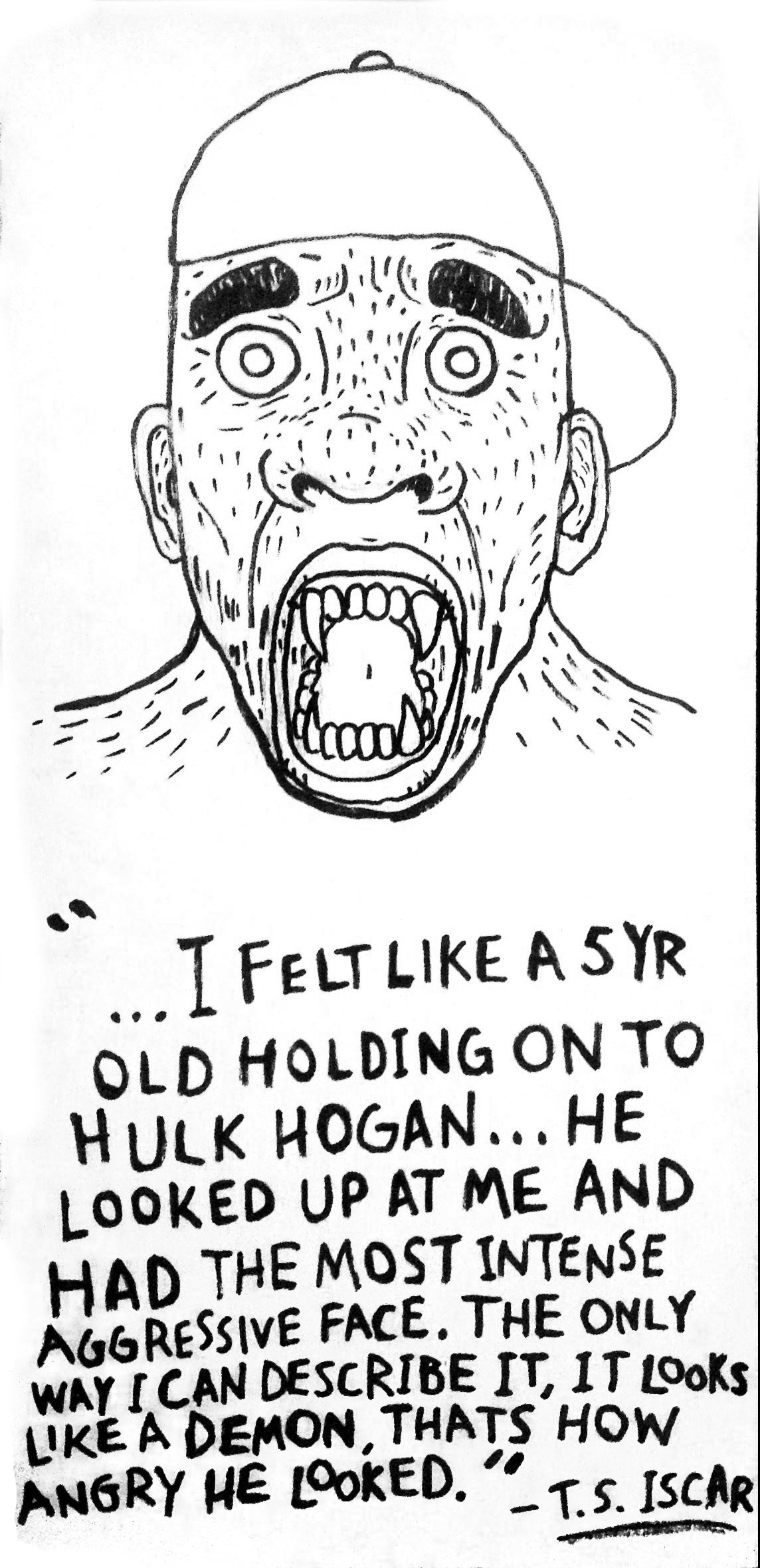

Yeah, I mean, for the most part I only had one instance when I was in Savannah, and it was one of those St. Patrick’s Day parades they have every year there, and I was walking with my friend (she’s white), and we were just walking through the crowd. And as I was walking past some white dude, I guess he shouted out to my friend “what are you doing walking with that nigger”, and I stopped and asked “what did you say?” and she said “come on, let’s go…keep walking.”

That was probably the only time. A lot of my friends came from all over the place—SCAD is an international place. That was my only thing that I dealt with there. But you know, I don’t think I was conscious enough to see other things that were going on outside of myself either. I don’t think you really think about these things unless you have any context for it, or read more about it. When I was younger, my parents surrounded me with literature about what happened, usually a lot of things like Martin Luther King and all this other stuff that we sort of already know about.

They want you to think that everything is fine, everything is equal, when in fact it is far from it.

High school did a shitty job of it. They barely wanted to even tap into slavery and how that truly came to be. I didn’t find out until later in my life, when I was an adult— and see that’s the thing. America does such a fine job of hiding all this dirty history, and then you come to find out it’s not who it says it is, then you have to question the system. And that’s the point of [this weak education], because they don’t want you to question the system.

They want you to think that everything is fine, everything is equal, when in fact it is far from it.

Part of the idea of this project is to track how the movement for Black lives has changed people’s lives. Did it change yours?

When everything with Trayvon Martin happened, reactions on social media were so varied—some people siding with George Zimmerman, and everything—it made me question my place in the world. So I took to Twitter, and learned a lot that way. I started to recognize that many people come from places that they haven’t had to deal with this stuff on this level before.

How did you learn to deal with it?

The only way to deal with it for me is through social media and talking to friends. I mean, I’m fine, I’m good—I’m just enraged, all the time, 24/7. When I’m seeing videos or reading articles of the murders of unarmed Black men, women, and children, with police going unpunished, and then seeing the media trot them out as deserving of this treatment, it’s maddening. I’ve found ways to manage it, but it’s always there in the background.

I’m fine, I’m good—I’m just enraged, all the time, 24/7.

I’ve tried to curate where I go and what kinds of people I have around me. It’s very hard to “get over it”—you know? We should confront it. It’s gotten people to open up, and have conversations about about it that aren’t really comfortable with it. We should have a public forum to discuss these things. To have a conversation where there’s no bashing going on, there’s no yelling. It may be a little emotional, but being able to talk through some of these feelings that, maybe that I have personally gone through, and for there to be an outlet, for [white people] to talk about it, in a way.

Because I think talking about it not only works through the the trauma of it, but you know, it’s also inviting them into it as well. So they understand the perspective. Basic or not, it helps, I think….

I think white people simplify the race relations to a point where it’s still harmful. You’re not getting it, and you’re not trying to empathize or try to figure it out. So public forums would be great, but also—what would we get out of it? What would be the end result? What will we decide to do from that point? How’re we going to change institutions to start looking at this in a more critical way?

Those things need to be addressed, especially when your life is affected, my work life is attached to it, my health is attached to it, the lives of my family, my son — his as well..I keep in mind that white people haven’t experienced being racially oppressed. But, keeping that in mind, they have to acknowledge that themselves, as well.

So that public forum would be very necessary. Vital.

Could you talk more about your son? How old is he?

He’s thirteen.

Oh wow. That’s an age.

Yeah. I had him when I was young myself. I was 20, it was in college. Having him has made me look at this in a very serious way too. When that thing happened with Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown, I saw people that were members of my family that it could’ve been. It could still happen to them. And especially to my son. And so I’m at a point of no return. I have to be involved, somehow, some way, to protect them. And others as well.

Did your parents talk to you about you’ll be perceived by the world? Have you had that conversation with your son, or will you? Do you think that what you’ll tell your son now will be different from what your parents told you?

It’ll probably be about the same, but in my way. I’m definitely different. But yeah, I had that talk. You don’t think about it when you’re younger. You just think about it as, “okay!” You just comply with it. You know, when my mom used to dress me really nice so I could look somewhat respectable, cleanliness, stuff like that. I had no idea what it meant, I just thought, “This is what you’re supposed to do!” But it was also to show that I can look just as good, or when it got to school, and she was very hard on me for school, I think part of it was survival. All of these things were survival tips. How to carry myself into the world.

I’m policing my own body to make someone else feel comfortable. That’s something that most people don’t have to worry about. White men don’t have to think about that.

As you get older and how that shapes you really shapes your view on the world. I know that I’m being watched. That’s what it feels like. I’m also very conscious of it myself. Sometimes I don’t walk very close to white women. I don’t them to think that I’m going to snatch their purse, or catcall them, or do something that makes them feel uncomfortable. So I’m policing my own body to make someone else feel comfortable. That’s something that most people don’t have to worry about. White men don’t have to think about that. At all. I’m constantly thinking about myself, and how the world views me.

I’m starting now to break that. I call it decolonizing. Trying to break down things that we’ve been told or raised to believe, or things that I’ve observed. To focus more on our human experiences. And try to actually live your life as who you are. Rather than what you’re perceived as.

Growing up Black, you feel that if you imitate, or appease whiteness, you’ll be spared. But you’re giving up a piece of yourself.

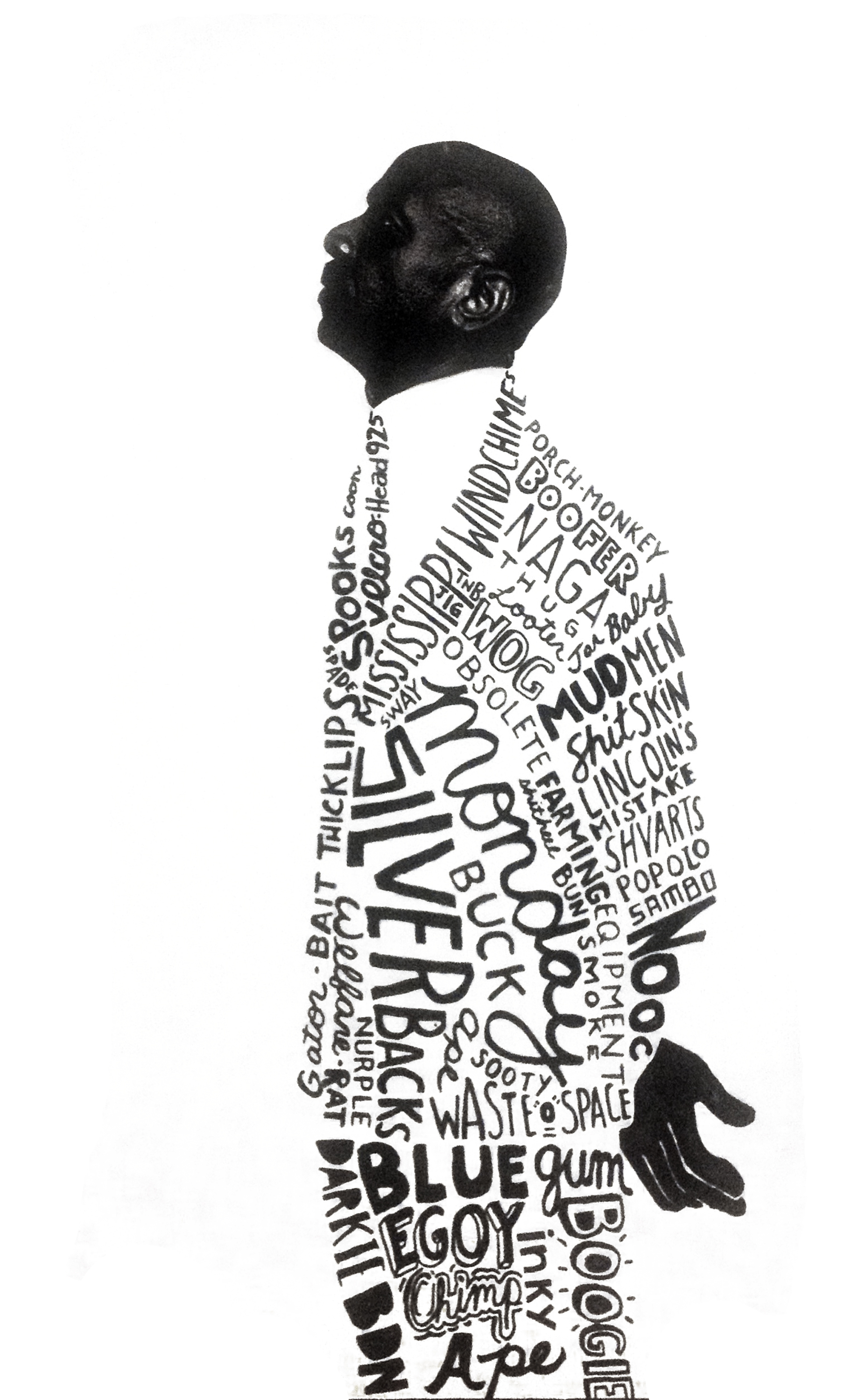

We live in a world that’s formed by whiteness and white supremacy. Growing up Black, you feel that if you imitate, or appease whiteness, you’ll be spared, I guess, or maybe you won’t have to deal with so much of the backlash of being a Black male, or a Black woman.But what I did not realize until later is that you’re giving up a piece of yourself. Giving up a piece of yourself that I have learned I have to love. This is my identity. And to not acknowledge that—a little piece of you dies inside, when you don’t.

I’m embracing the hell out of it now. And I think every Black person in this world should. Even though we are in a world of anti-blackness. And I think that’s why there’s so much outrage.

Because of all the things that we have gone through, that a lot of people just sort of brush off, but they don’t realize that we live in a world that is anti-black. This has been established since colonial times. And has mutated into many different things within our system. And if we don’t acknowledge it—because it’s still going on—if we don’t acknowledge it, we go into these systems, and try to reform it.

Personally, I don’t believe in reform, because it’s like putting a tuxedo on a turd. It’s still a turd, it just looks like a very nice turd. I think a lot of things have to be dismantled. You have to recognize the history of the state of anti-blackness. And why now, there’s still so much oppression going on. How to acknowledge that and how to fix it. And I know government and policy and all that, it’s a slow drip, but it has to start somewhere. It has to start today. Right now. Like, yesterday.

Have you participated in any activism?

I went to three protests towards the end of last year that happened in New York. Especially after the Eric Garner announcement, when they announced the verdict. But that was the last time. I’ve donated to a couple of initiatives, Tamir Rice, and one other one too…helping [Marissa Alexander], who was accused in Florida of firing the warning shot. I donated to that.

I recently donated to what’s happening in South Africa, with the tuition feesthat were going up. I realized that the stretch of anti-blackness is international, and when I saw what they were doing over there I was inspired by that.

But I haven’t been to any protests since the ending of last year. But I wanna be more active. I’ve been starting some creative work as an outlet for me as well. I think there’s not much of an outlet in graphic design with it, but I still do use those skills. But for me, not only just talking about it with my friends, or just talking about it with people in a public forum, making artwork really helps. It’s almost therapeutic.

And it’s very difficult to do in a subject like this, making artwork, on this level. It’s sometimes very hard for me to do, emotionally…it’s a physical manifestation of what has been happening and how it’s affected not only my life but the lives of others too.

One of the things I thought about doing is—because I’ve been involved in teaching for a while—somehow do it through a creative way. Working with minority students, a lot of them don’t particularly look at the creative field as a job. If you think about graphic design, it’s fun to do in class, they think of it as an elective, maybe, but they don’t picture it as a job. And I think the design world has a particular minority problem, in my personal opinion. So I’m trying to figure out how to send minority kids to do the work that I do, and be involved—focusing specifically on them—and how to be involved in other ways.