Marvin Touré

Could you tell me about your artwork at the School of Visual Arts?

My work in general—it’s how I understand life. It’s how I go through life and make sense of the craziness that happens in the world. And it’s stuff that not until I recently, I realized that, okay, this is art. Which is why I came to grad school!

Because of my background, being West African, being from the Ivory Coast, my parents being from there, but me being born in Maryland and then growing up in Georgia, all of that filters into the work at some point. Being Black in America filters into the work because it’s a very real factor in my life, and it affects my day-to-day. And it’s not something that I can turn off and on, and say, “oh, well, I’m just gonna turn that off and I’m not gonna think about race.” It affects me. It affects my life and going through society.

Being Black in America filters into the work because it’s a very real factor in my life, and it affects my day-to-day. It’s not something that I can turn off and on.

So, in coming here, the piece that I made was me kind of trying to make sense of what I had been encountering when I got here. First day I walk into the building at SVA, it’s a group of us, I’m the only Black person in the group. It’s a lot of Asian students, a lot of white students. I walk in, I get stopped. And since I’m from Georgia, I already know. ‘Cause the Black security guards already know what it is, ‘cause it’s like, “oh, those are the faces we kind of know they go to school here, but you…[makes clicking sound] You look like,what’re you doing here?”

Now, they know, because I’m one of the only Black faces here so they’re like “oh, hey! Oh, you can go now!” But before, it was like “excuse me, I need to see your ID.” Like literally, one time I was in front of the desk, walked outside the door to say hi to somebody, came back, “can I see your ID.” It’s ridiculous…

White supremacy permeates through almost every facet of our society, and art is no exception.

So, making sense of that, and then also, coming to art school—it’s the art world, it’s supposed to be so inclusive. It’s supposed to be a grand place of, “we accept the people that society doesn’t really accept. We accept the people with the crazy ideas, we’re all fun-loving; we are the world; we love everybody; we got vegan Doc Martens, we go get our gluten-free bagels in Bushwick and we chill and sip Starbucks and all that, and read literature.” You know, educated people! Who are kind of kooky at times. So you would think that this is an environment that’s receptive to otherness. Where you’re not made to feel different. But, white supremacy permeates through almost every facet of our society, and art was no exception…

There haven’t been Black students in my program, for like, eight years prior to when we came: me and Dareece Walker, Delano Dunn, and Tia Daniels. Before we got here, us four, you had no Black students for a while. So the shock of having these faces here, now, and not only the faces but the nature of our work, was a little off-putting to some people. They were just like, “whoa!” You know?

Some people were super excited. You get some white students that we like, [claps] “you guys are here!” And it’s like, your overeagerness bothers me a little bit. Chill out….

And we got comments, a little bit, about affirmative action. It wasn’t specifically about affirmative action; it was like “oh, it’s good that we have Black students here now. Isn’t there something that companies have to do, to get a certain number…they have to hire…a certain number of people…applicants of color…”

You get these kind of subtle comments. And, you’re like, I already know where this is coming from. So, all of these kind of affected me, as I think they do a lot of people of color. It’s one thing picking your battles and letting stuff brush off your shoulder. But when that stuff starts to pile up, at some point you have to deal with all of that! At some points I’m like “whatever, whatever, whatever,” and then at some point I’m like “this is just—what the fuck is going on? Really? This is ridiculous.” …

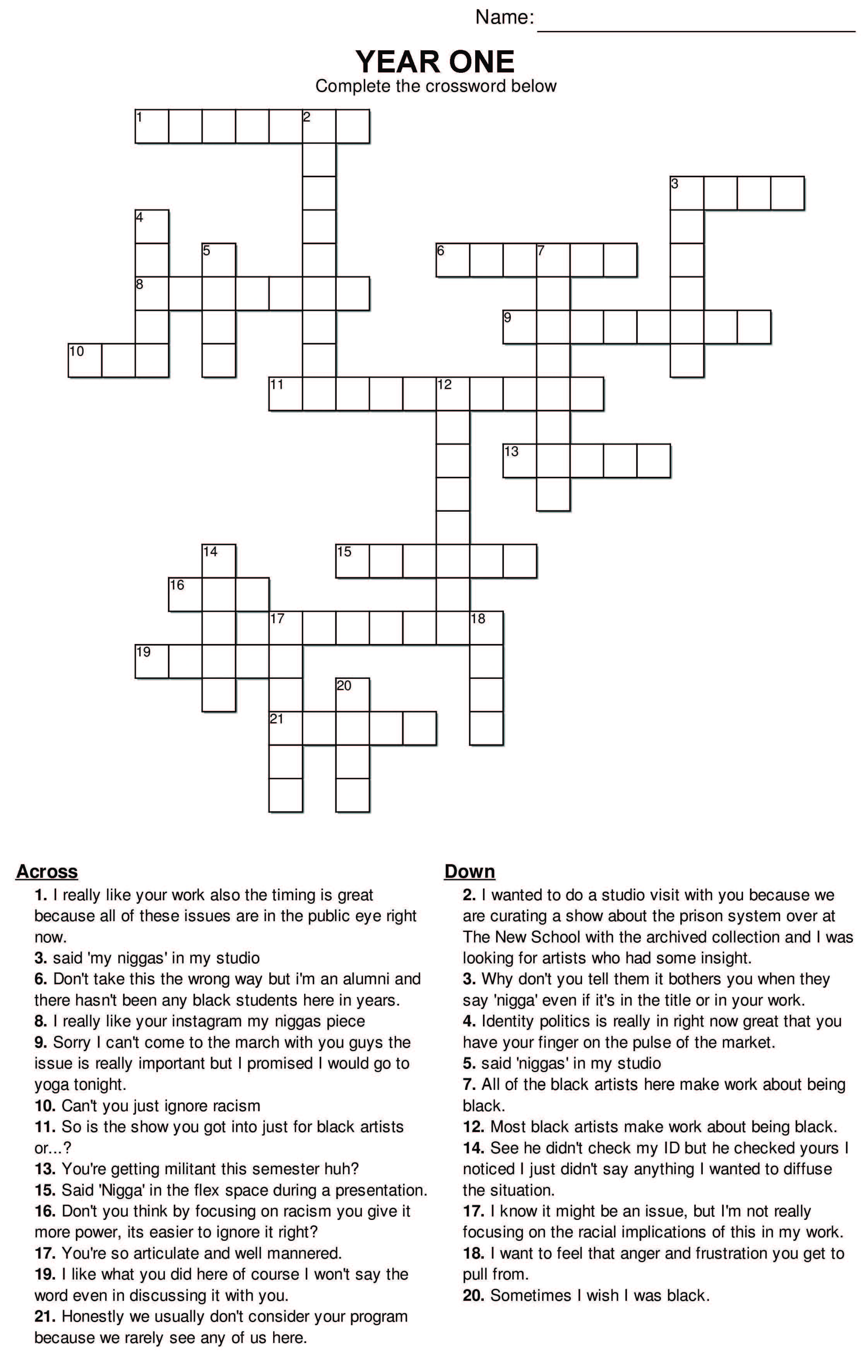

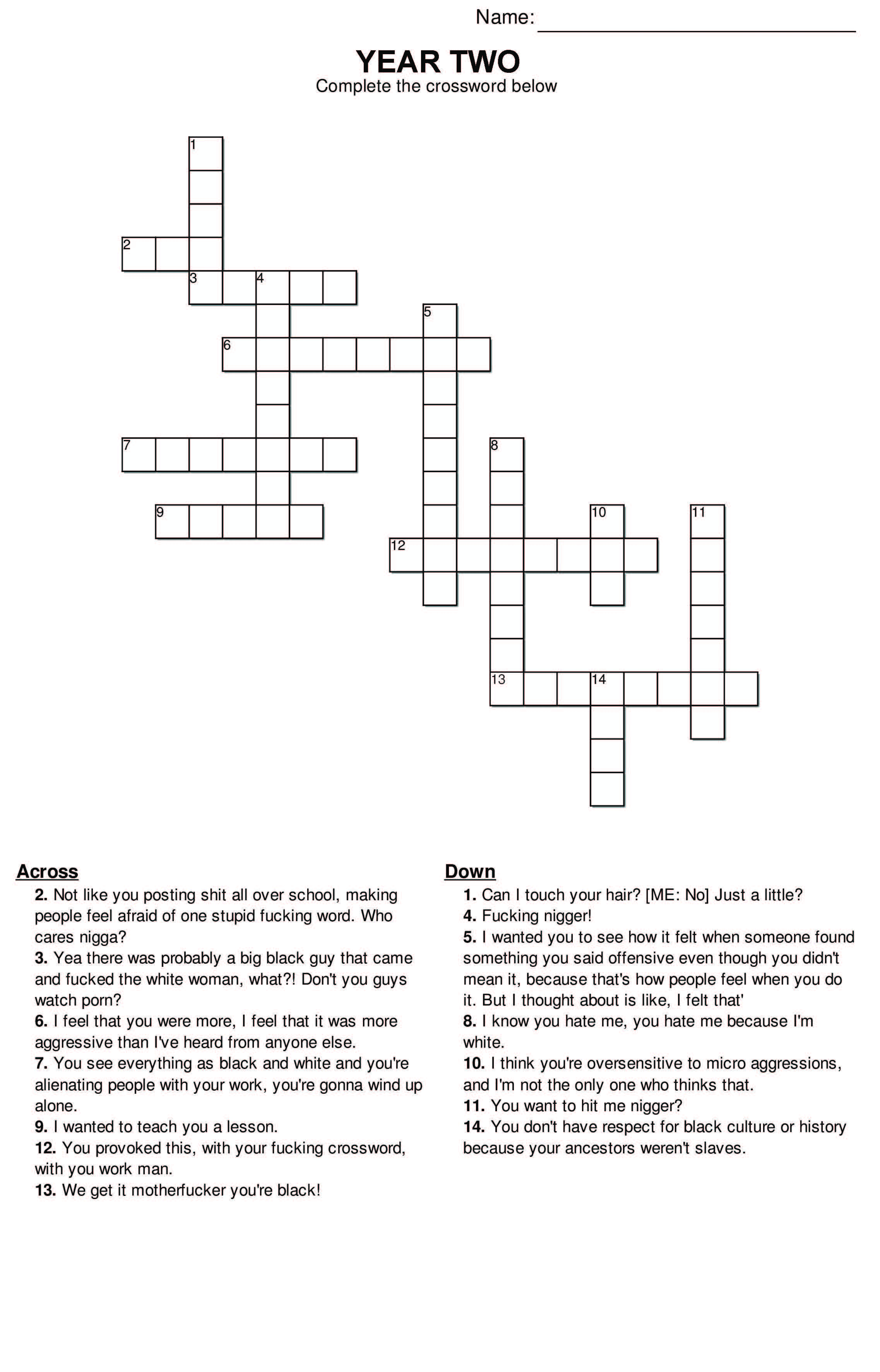

So I just started writing them down. ‘Cause I write a lot. I have mad sketchbooks, so I just started writing things people would say to me. And I remember shit. I remember it. If somebody tells me something, and it sticks with me, I’ll remember what they said, and I’ll remember who said it. I can’t speak for everybody, but for me, I can remember the first time I was called a nigga. And I remember the times after that I was called a nigga. So I remember times where there’ve been flagrant racist statements made, and I remember those instances. It’s not something I can just bypass in my memory. So, because of that, I jot it down. And when it came to making the work, I was like okay, I wanna do this crossword puzzle, but the answers are gonna be the names of these individuals, and the clues, like “across” and “down,” are gonna be everything they said.

So I did that, and the question of “am I gonna have the key shown in conjunction with the piece.” was the most important thing in the piece. And then I thought to myself, “is this a piece to publicly shame, or is this a piece to put everybody on notice and make them think about what’s going on?” And it was the latter. So I hid the key…In the actual piece [on display] in the hall I didn’t want everybody to know. ‘Cause it’s not about everybody knowing who said it; it’s about knowing that these things were said. And these are people in the program—professors, studio visits, students.

And when I did it, everyone was kind of, “whoa,” they were like “really? This happens.” I’m like “yeah….I didn’t make all of it up.” …What I didn’t plan for, and didn’t expect to happen, was some of the reactions. People started asking, “am I on there?” People were like “hey, am I—is my name, in the actual…crossword puzzle? Can I know who’s on there?” I’m like, “no.” …For them, they felt uncomfortable. Some of the things on there were really messed up….

What’s funny, is that what started out as a piece to look at these microagressions turned into a two-year project, me detailing microagressions in my graduate program. And when you look at both years, year one has a lot more than year two does. And it’s not so much that people just all of a sudden they’re like, “okay, we’re not gonna say crazy shit no more.” No, it’s because a lot of people just didn’t talk to me anymore.

So it’s that kind of thing. And because of that, I stopped also talking to other people. I withdrew socially in that regard, and so did people, they withdrew from me. So, when you look at the the two, it’s almost like year two has more egregious—really overtly, super racist, charged comments that are on year two. But it’s a lot less.

How often do we have the opportunity to intervene in that way?

Our Black Student Union here, the school is both grad and undergrad, and…it’s interesting to hear the undergraduate Black students here talk about their experiences with some of the professors. How they’ll have crits and they’ll maybe talk about, or bring up, the notion that there’s no representation in terms of faculty, in terms of the artists they study, or how the lack of diversity in terms of the classes, like students, makes it hard to get crits because people sometimes don’t know how to address people that make work that talks specifically on social issues. And they get crazy pushback, like very aggressive: “why don’t you think your white counterparts can talk about issues that pertain to your community?” Or, “you don’t think they understand?”

Kind of taking it lightly that there’s a lack of representation in terms of the faculty…”And in conjunction with that, we have no artists of color that are represented in the art and what we’re studying, and the canon of history. Maybe that has something to do with it!” And they don’t even know where to enter to even discuss to give me any kind of constructive framework to take my work to the next level.

It’s so hard…I do think that, obviously, everybody can find an entry point into the work. But at the end of the day, it’s just a different lived experience for minority groups than for privileged groups.

I’m starting to think of empathy. Can you empathize with the work. With somebody’s point of view. And, I feel like when it comes to creating artwork in general, people enter it from whatever they wanna enter it into.

I like making things that are not only aesthetically pleasing, but they have a very deep social message, and they’re very personal to me. I kind of got that growing up on ‘70s reggae. The music that you listen to—Bob Marley, Black Uhuru, Third World Band, Peter Tosh—these songs sound awesome, they’re great, you just wanna bob your head, you wanna dance, they’re nice upbeat songs, but what they’re talkin’ about is really socially conscious…And it’s really dense subject matter if you wanna start to unpack what they’re talking about. ‘Cause it’s not just spirituality, it’s also social issues that affected Black people in Jamaica and elsewhere.

It gets quite frustrating when you’re paying as much as everybody else is to be there, and you want the same kind of artistic dialogue around the work, and you don’t get it ‘cause people are too scared to deal with fuckin’ racism.

So, in talking about that and having these kind of things that play, where it’s aesthetically pleasing or sounds good, deep in content—people will enter at aesthetically pleasing. They’ll look at the formal qualities, be like “oh, this is so beautiful,” or, “I like this,” or “mm, I think you should move the right side up a little bit more.” Those are the kind of things. You have to force people to engage with it on the conceptual level. Dealing with social issues. ‘Cause at times, the work implicates them. And people don’t like being told that they’re wrong…

It gets quite frustrating when you wanna have a crit, and you’re paying as much as everybody else is to be there, and you want the same kind of artistic dialogue around the work, and you don’t get it ‘cause people are too scared to deal with fuckin’ racism.

I think one of the most rewarding things for me was [during the open studios event for the MFA students] when this mother came in with her daughter, and was looking at the four of ours’ work, and she was teaching her daughter about different aspects of the Black experience in the United States through our work. And she was almost in tears, like “thank you guys for making the work you made.”

Turning towards education, I’m interested in the free speech debates surrounding the recent protests, and how they may or may not interfere with the function of the American university. What is the point of college? And how do the recent protests interact with whatever the nebulous “point of college” is supposed to be?

I mean, I think that in the conversation of free speech, people want selective free speech. Right? So, the institutions are all for, or will back, free speech when maybe a professor will say something that’s racist, or borderline, like a microagression or something. [That] is protected under the umbrella of free speech, but then when students will come back and say “hey, by the way, this is racist, let’s have a real conversation about systematic racism, let’s have a conversation about the Ivory Tower, let’s have a conversation about all these things,” that’s when it’s like “oh, wait, you guys need to chill out, why are you saying all this; this stuff is hurtful.”

So, when is it that you can and can’t have free speech? You know?

Absolutely. And potentially, it has a lot to do with race, but also, generational differences. Every generation shits on the next one, you know what I mean? People don’t like to see the things that they’ve always held to be true get questioned, one, and two, I’m sure that to a certain degree there’s some amount of just assuming that because these students are not white, or are younger, they don’t understand how things are supposed to work. And so they don’t get why it’s so important that we do things the way that we’ve always done them, and I think the protests are about saying that that’s not true.

I was listening to Don Lemon and others on CNN talking about when this younger generation, these millennials of color, talk about things like microaggressions and covert racism, “what does that really mean? And is it really important, in the broader scheme of the fight for equality?” And they usually wrap that argument in this notion that “we went through worse back in the day. And back in the day you should’ve heard what they said to us on college campuses. We pushed through, we marched in the street for stuff that really mattered. We were marching for Vietnam, and we marched for equal rights, and all of this other stuff. And affirmative action, everything like that. But now, you guys are talking about somebody saying something subtle to you, and you guys are all in your feelings, it’s this generation of sensitivity, this overly-sensitive generation—what is that about?”

So, this buzzword, of being an oversensitive generation, is starting to creep into a lot of things, even to the point now where millennials are starting to use that terminology. Mostly white millennials, starting to use that terminology towards when people bring up issues of race. Like “oh, we’re just in a sensitive generation.” You’re starting to hear that more and more, and I look at that as—this is ridiculous. ‘Cause you’re diminishing some very real emotions, and you’re diminishing the power of words. Like, how a microagression is like a seed, can fester into something way worse. You’re trying to just bypass that altogether…

I think that in addressing the little things, the more those are being addressed, the better we will be for it.

And people definitely don’t get the way that that can just wear on you all the time…These are things that you’re constantly aware of all the time.

How can Black people as a whole—not saying it’s a monolith—but how can the “community” heal, or get over racism, when we’re reminded of being an other every day, multiple times a day. I can’t just, one day just like, “oh, I’m human,” and look at it like that. I’m constantly reminded not only that my skin is brown, not only that I’m a Black man in America, but what that means. And where my place should be. You know? It’s really a problem, and I wanna discuss that.

I’m constantly reminded not only that my skin is brown, not only that I’m a Black man in America, but what that means.

**How do people expect to heal without talking about it? When people don’t want to address the legacy of slavery or of Jim Crow, they want to say “that’s all in the past now.” But if we continually don’t talk about these things, and don’t actively try to find solutions, then how can we get past them?

That’s a universal truth. Like if you’re in a relationship—**

That’s what I was about to say! [If you’re in a relationship] and you don’t talk about the problem, it’s gonna be there. It’s not just gonna go away overnight.

They say not to go to sleep mad. What do you think we’ve been doing for the past 60 years since the Civil Rights Movement?

Like “I don’t know, just get over it, it’s fine!”

That’s why the Black Lives Matter movement on the whole and the college protests specifically are great—because by forcing us to have to keep talk about it, they’re forcing people to feel the guilt, or at least the irritation of it all the time. Which is something that we’re always experiencing, so you can experience it too.

It’s so funny for white people to get uncomfortable about the race conversation. You can see it in the room; people try to sink into their chair, they don’t wanna have the conversation, and I’m like, “you realize that I have to do it every day.” This is just like a regular one-hour conversation, if that, and you’re uncomfortable.

You can walk away from this, and I can’t.

When I first came to school here, I was making work about gang violence and child soldiers, and I made work about Black leaders, and then made some work that was more personal, but it was about race, and it was always me talking about my Southern upbringing, and racism I felt down there. And everybody here is like, “yeah! Those people in the South, oh my god, they’re so crazy! What! Really! I can’t believe they said that! In Georgia! Aw, that’s ridiculous! It’s just wild! Why would they say that!” It’s almost like this view of the South like it’s uncivilized, in a way. The people “down there,” they’re uneducated, that’s why they’re acting so ignorant. Why would anybody say that to you.

But then, when I turned the lens on the institution that I’m in currently, I made the work about what was happening within the program, everybody’s like “what…the fuck…is going on? Really?” And people get upset, and it made people very uncomfortable, to be in a space that they thought was comfortable for them. And I just fucked up their vibe. I killed the vibe ‘cause I was like “Hey, by the way, guys? There’s some stuff going on here? Can I draw attention this real quick?” And it definitely affected how some people acted. They reacted towards me and the work that I was creating.