Jarrett and Jon Key

Can you each tell me a little bit about yourself?

Jarrett: My name is Jarrett Key, I have a twin brother, his name is Jonathan Key. He’s sitting right next to me. I grew up in Alabama for most of my life. Did construction work for most of my life. Went to high school, got a full scholarship to go to a college prep school. Jonathan did also. Then I went to Brown where I studied public policy and theater arts. I actually went to Brown thinking I would be an opera singer. Then I decided being a Black tenor wouldn’t be something lucrative…I saw this documentary and it was very discouraging. But it was totally fine because who wants to be an opera singer anyway. Now I work at the Public Theater. I’m the assistant to the associate producer there. I live in Brooklyn. I am the producer and director of Codify Art, which is a multidisciplinary artist collective. The collective features mostly—actually all people of color and queer people. Which is crazy!

How about you, Jon?

Jon: My name is Jon Key…I’m a black graphic designer, art director, writer…I do design direction at Codify Art, I love theater posters, I love making books, I love doing projects and work about heritage and identity and culture. Those are topics and things that I try to delve in with my personal work and other work I’m making with people.

Have either of you been involved in activism before last year?

Jarrett: In some smaller ways.

Jon: Yeah, definitely.

Jarrett: For example, in high school. Having put together some kind of fundraiser or bake sale or something like that for a politician.

Jon: Yeah I remember we definitely did that for Obama. Even like in college, I feel like there were many opportunities. I feel like I was participating in activism the same way I participate in activism now. I’m not a protestor, I don’t go to marches. Way too crazy for that, it makes me really uncomfortable. I like organizing events and sharing information and making work about it.

Jarrett: Yeah, definitely. Being a Resident Counselor at Brown, definitely putting together events to highlight issues that important to me, to provide educational opportunities for my residents. But I don’t go out as a protester. For me, making art or organizing events is something I’m good at, so it’s something I feel like I can contribute a lot at.

Jon: It feels like a productive way to deal with issues, by actually making work, actually trying to talk to people, actually trying to have discussions around it. And I feel like that’s something that I’ve been doing. I think one of the great things about Black Lives Matter is it’s the first time it’s erupted as such a big issue to so many people in such a big way. Whereas before it didn’t necessarily feel like the activism I was doing was part of a larger conversation

Jarrett: A national movement. It actually feels like the art that I make is a part of a national conversation.

It’s not so much important that people are paying attention to your art because it’s art, it’s important that people are paying attention to it because it’s part of this.

Jarrett: Exactly. My art also happens to be in conversation with the things that are also important in national issues. And have been important to national issues, so thank God we finally got some spotlight.

What do you think of the growth of the movement over the past year?

Jarrett: I have a very complicated relationship to it. I think because more emphasis was put on it a year ago—on police brutality, on killings of trans people of color specifically—I think because there’s more focus on it, now suddenly everyone is talking about it at any moment that it’s happening. So I don’t necessarily know that it’s a sustained thing so much as that it’s our reality, and now we’re just paying attention…I think the Black Lives Matter movement is at some points very topical and media-focused, and people get very excited and riled up about it, and when that happens it seems like it’s going really well. I think now we’re in a time where it’s less topical, unless you’re thinking about it in terms of politics—

Jon: If you don’t follow those [platforms] that are that type of content then you might not actually see it.

Jarrett: Exactly. For me it doesn’t feel like it’s as pervasive via social media than it used to be.

Jon: But I definitely think that it’s on people’s consciousness more than it used to be.

Jarrett: Absolutely.

Jon: Which is great. But that’s what I was gonna say, that I think it moves in waves and shifts of being extremely topical and extremely on the front end of most people’s minds, and—for us it’s the reality that we think about every day. Of course, I’m walking down the street, of course I’m thinking about this. It affects my life. I think that it’s still nice that people are still moving and rallying behind it. Marches are still happening, protests are still happening.

Jarrett: People are asking politicians the hard questions about it.

Jon: Yeah, I mean, it came up at the [first] Democratic presidential debate. I really like that, I appreciated that, I loved that, but at the same time I wish that every single person was asked that question.

**There seems to be a spectrum of how people handle the movement. Some people feel like just talking about the issues and bringing them to the forefront is enough, and others are more interested in a more radical approach–”burn it all down.” Where would you say you fall on that spectrum? **

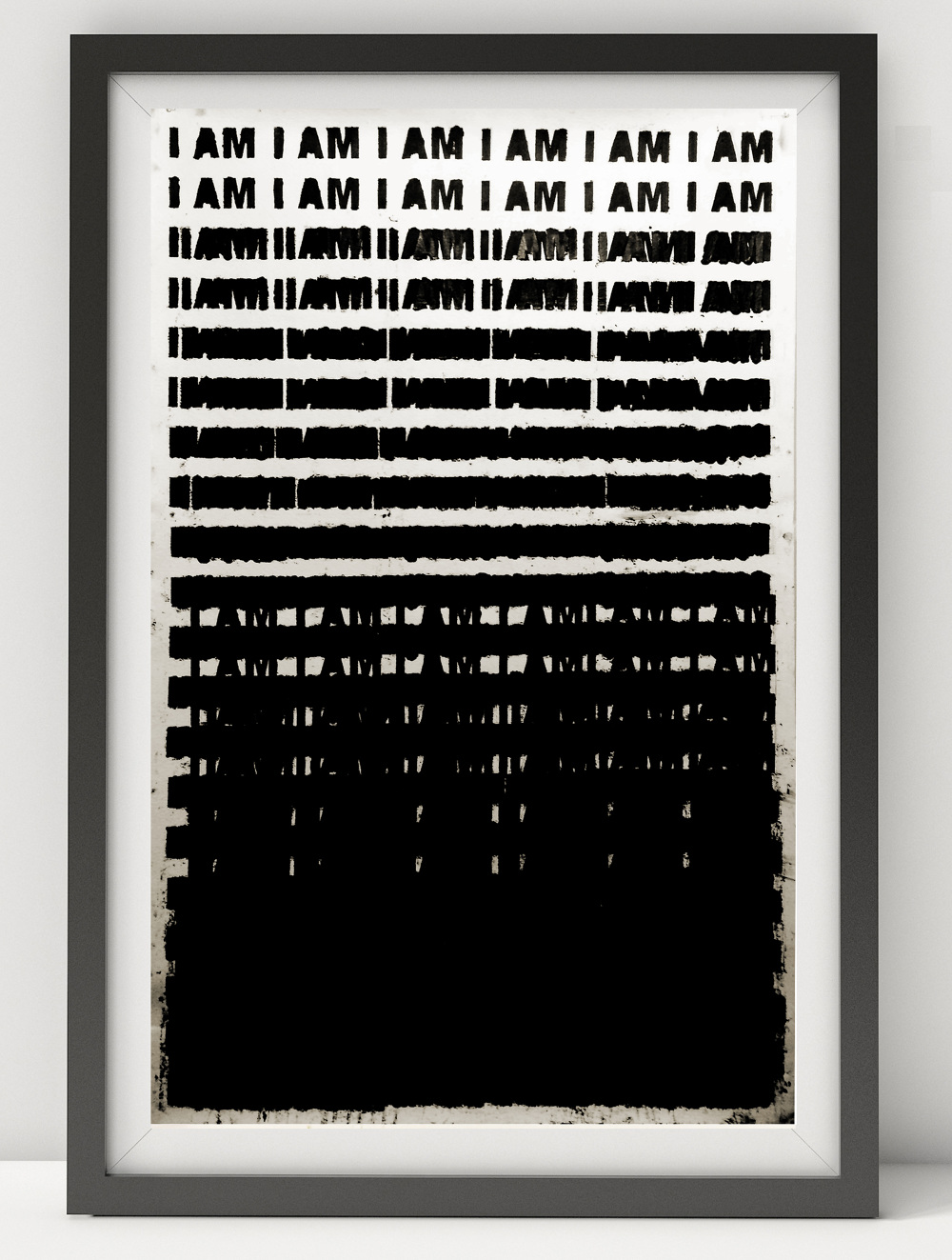

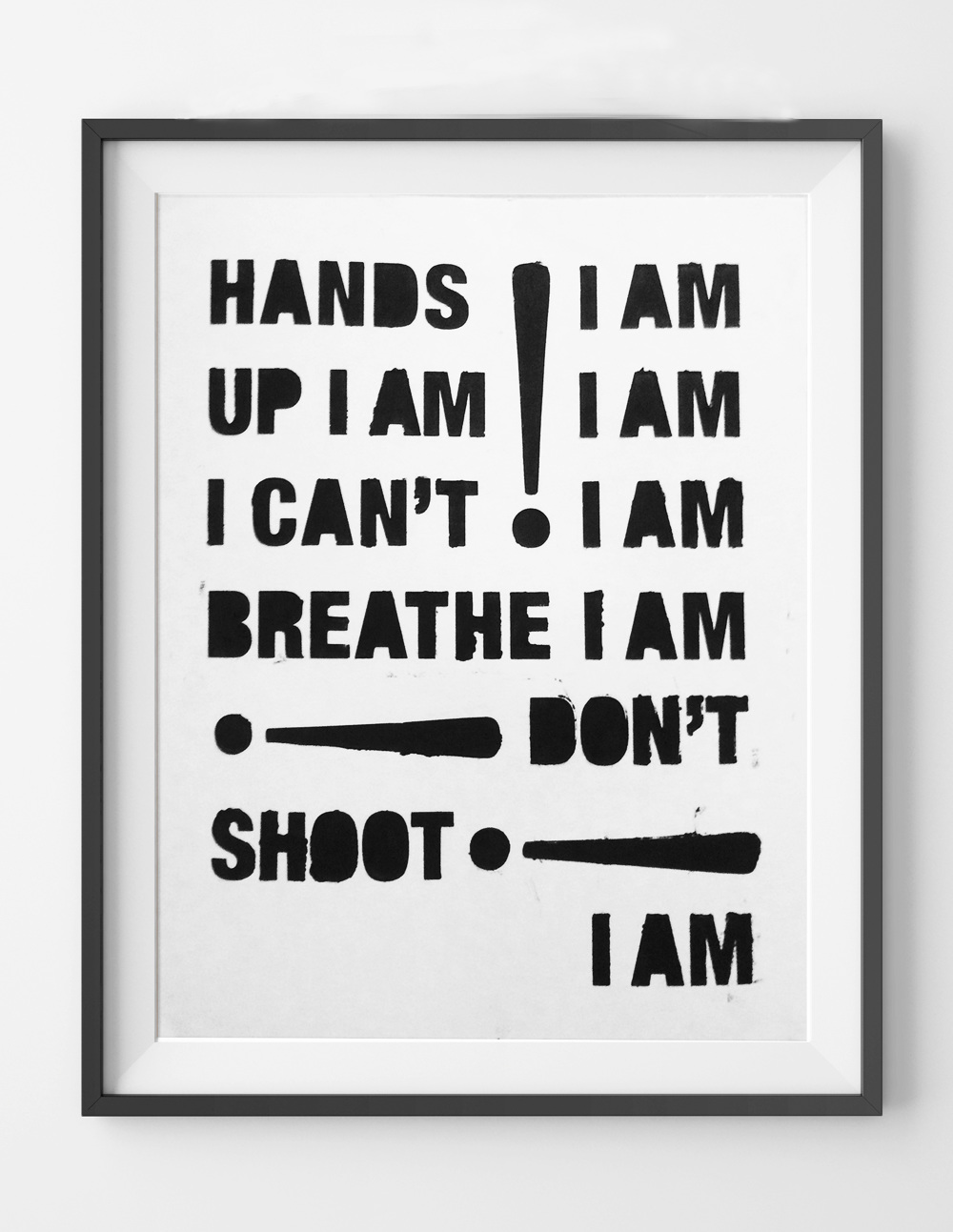

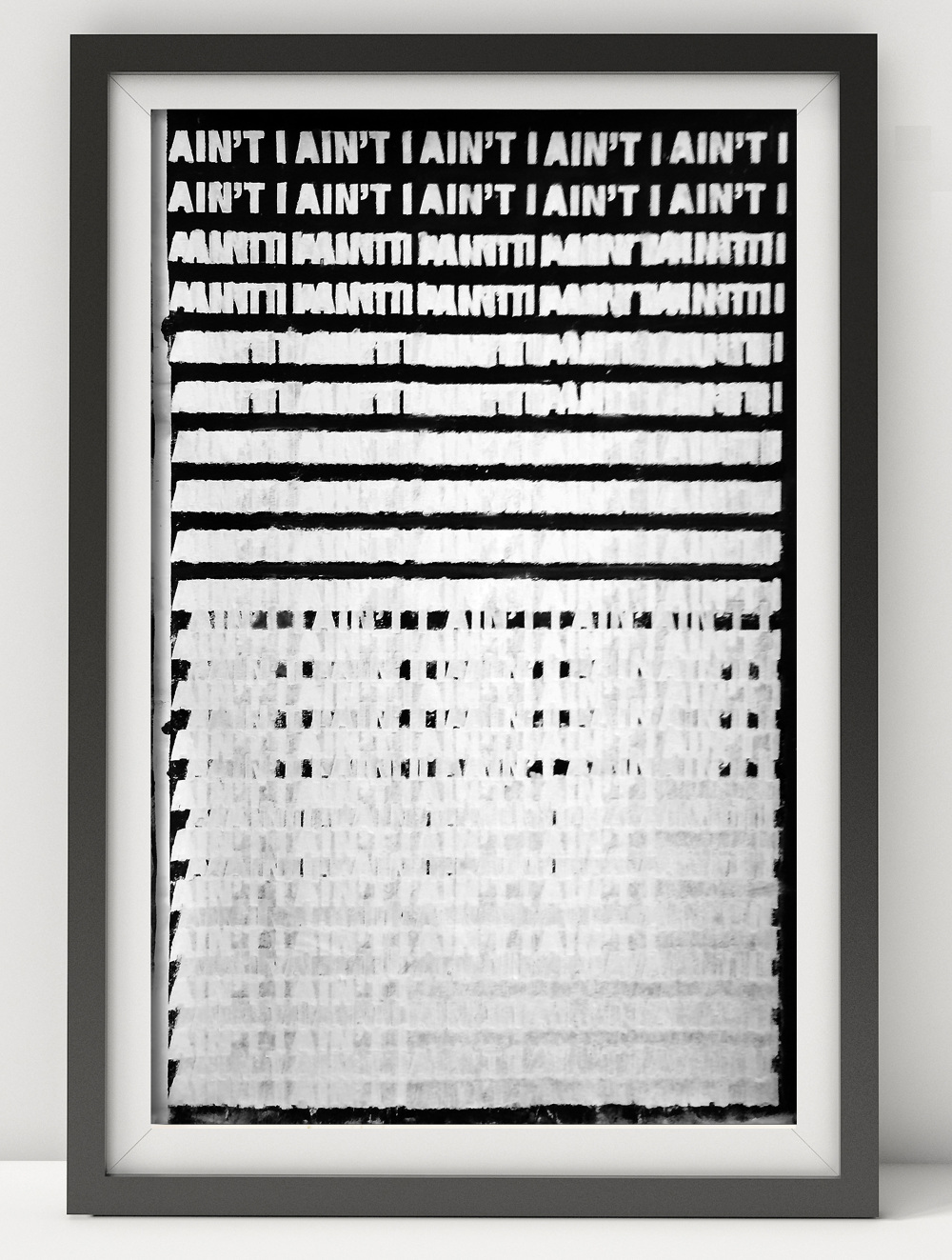

Jarrett: I wanna talk about this in terms of my art making as a frame, because it’s too hard to do it any other way. For me, my art is right now inherently political art. I think the function of my art is to talk about equality for all people, but specifically Black people. So I’m dealing with notions of “I am”: ”I am a man,” “Ain’t I a woman,” those kind of large statements of “I take up space, I deserve equal rights.” And that has less to do about police brutality, and more to do about me as a Black queer man, being worried that people will not respect me or give me the rights that I deserve to have.

Being afraid to do x, y, and z. Dealing with, “how do I personally fit in this narrative that people are going to be creating about me or about my generation in the future?” And, “how do other people see Black faces in this generation and in the midst of this historical context?” We are people; we deserve to be recognized on a human level. Which is kind of “burn it all down.” I actually do think we should probably burn it all down, honestly. But I also think that it extends way past police brutality.

I think that police brutality is a side effect, a symptom of a larger racial dynamic that has happened for years in the U.S. That is not the problem. The problem is that people in this country don’t actually value the lives of people of color, period…I am just trying to push for, “I am human, this is how I am, you should be able to accept me for how I am regardless of what your standards and expectations are. Stop assuming things about me, let me show you and tell you what I am, and you can take that and move forward with that.” That’s what I’m fighting for as an artist with my work. And that’s what I want for my nation.

Police brutality is not the problem. The problem is that people in this country don’t actually value the lives of people of color, period.

Jon: I’m definitely on the spectrum that it’s more than just going out and talking about it…The work and the projects that I do, we are trying to make art about it, we are trying to get other people to make art about it. And I feel like for me that’s a very productive way to create images to rally behind police brutality.

Also with my own projects, like with We Are Bulletproof —my manifesto says that we should fight. It’s not always physical fighting, but I definitely think that because of the level that people are talking about Black Lives Matter, people feel like it’s topical and they don’t really want to talk about it, they just feel like it happens in the news, and then you have people that live it. For the people that live it, it’s scary. And that’s where this fighting comes from.

Jarrett: To not fight is to die.

Jon: To not fight is to not care. It doesn’t matter to you. You’re giving up. I’m not a “burn it all down” like Nina Simone—”are you ready to kill?”I’m not like that, because I think that lives are important, but we have to do more than just have a little talk about it.

To not fight is to not care. It doesn’t matter to you. You’re giving up.

There’s a lot of reclaiming that I’m trying to do through We Are Bulletproof. It was made because I’m afraid. Sometimes it doesn’t even exist on a national scale. Sometimes it’s on a personal scale. That project started off as a personal project for me to deal. For me to become more comfortable, for me to find community. To try to create community and connections with people, to remind myself that I’m not alone. And even though that doesn’t feel like a large thing, I feel like it makes a big difference, engaging your community in a way that you’re saying “we’re still here together.” To me that’s like you’re not trying to burn things, but you’re not being passive—

Jarrett: —and accepting what happens to you as if it’s your fate.

Jon: Exactly. I feel like there’s engaging that still needs to occur, I feel like there’s still a lot of work to be done, I feel like there’s still fighting that has to happen. But I know that it’s not possible for us to burn shit down to get us there. Everyone already thinks that we just burn things, steal things and loot things anyways. And that’s so crazy. Like first of all, don’t think that. People do loot things, and things are fucked up, but that’s not the crux of what Black people are. We’re not people that loot things. Those are the narratives and the images and the portrayals that surface the most. And no, just having the conversations that are like “no, this is not what the issues are about.”

How do you feel about the disruptive tactics being used in the movement?

Jon: I feel a lot of ways about it, but mostly I feel like I love them. I wouldn’t necessarily do those things, but do I think those things are important to drive discussion and for attention to be put on those issues? Yes. I think interruptions and disruptions and bringing attention to issues and forcing people to confront them on major scales are amazing.

Jarrett: It’s an important part of peaceful protest. That’s literally what peaceful protest is.

Jon: Literally. At the same time, do I wish sometimes that they were handled in better ways or different ways? Sometimes. But at the same time, when you’re shutting down a road, I’m like, “fuck yes, shut down that road.” But for example, I remember when the Black Lives Matter movement people went and interrupted the Bernie Sanders campaign. Bernie Sanders has been an advocate for Black Lives Matter. He cares about it.

Jarrett: He just cares about American citizens.

Jon: People are being like “why are they going and interrupting him; he’s been on their side. Don’t you think that’s so rude and disrespectful?” And like, no. I mean yeah, sure, it is rude and disrespectful to do that, right, but it’s protest. And at the same time, it’s like, no, still confront him, and make him continue to say it.

Jarrett: Don’t make it feel like a topical issue.

Jon: Don’t make it feel like it’s underwater, and it’s cute when it’s in front of a camera. Interrupt his ass! Is that something that I could physically do? No.

Jarrett: Is it something that I would be interested in producing? Yes!

Jon: Exactly. I don’t know if I wanna go on the stage as that person, but do I wanna organize something like that? A really powerful tool? Yes. Do I feel like that’s the only method? No. There’s a ton of ways to do it. So, yes, interrupt people, yes, protest, yes, shut shit down, because otherwise, it doesn’t matter. And also our country is media-run anyways. So in order for it to stay in the media, in order for it to be topical, you have to do crazy shit in 2015. That’s also just the reality of it. It’s all performance. Everything.

As men, did your parents have that kind of talk with you as a kid about how you were going to have to inhabit Black male bodies?

Jon: Absolutely. Growing up there were always rules that we had to abide by as Black men in our society. We had to dress really well all the time, you have to talk a certain way, you have to do this, you have to do that. All these things. You have to always be better than everyone. Jarrett: Better than people’s expectations or assumptions about you.

Jon: That’s exactly what they were getting at—you have to be better than people’s expectations of you. And if not then people will not give you as many opportunities, because they’re just gonna lump you in with how they think about Black people. So it’s always this idea of—

Jarrett: Fighting the stereotypes.

Jon: Fighting the stereotypes, fighting to be the best. We grew up in the South, so it was obviously a conversation that we had to have, because it was our reality. We lived in the South, went to an all-Black elementary and middle school and then an all-white high school. Shit was crazy. I don’t wanna go through all these stories, of me having a lot of crazy racial confrontations…but they happened. They happened from people that I was dating, to their parents—all of us have those types of stories. So it’s something that’s very much instilled in us, our reality, that we have to be conscious of. If you’re not aware of it, that could be it.

Jarrett: That could be the end of your life.

Jon: That could be the end of your life. Being hyper aware of it, actually. And that’s just exhausting. You have to navigate the world being aware of every gesture, every motion, every movement, every piece of clothing that you put on, the way that you talk. Those things can’t save you. But of course for your parents they teach you these things because they want to keep you safe.

It’s just exhausting. You have to navigate the world being aware of every gesture, every motion, every movement, every piece of clothing that you put on, the way that you talk.

Jarrett: They wanna arm you with the tools that they think will help you survive. It’s tricky.

I’m just thinking about racism that I encountered growing up. Which was, we were in first grade, we were on a baseball team—Jon and I both were on this team—and this little white boy was passing out bubblegum. To all of the people on the team. And we were like, “oh yeah, we want gum! Thanks!” And he was like “oh, I’m not giving you gum. I’m not giving gum to you because you’re Black.”

Wow! He just laid it out!

Jon: Seriously!

Jarrett: And I’m like six years old.

That’s rough. All of this is hard to put up with all the time, emotionally. How do you cope?

Jarrett: To cope, I’m making art about it. For me, coping is taking the time and space to be reflective about how I actually feel during this period of time that we’re in right now. It gives me the opportunity to cry alone if I need to cry, to be expressive the way that I need to be expressive in order to get out my frustrations regarding x,y,z; and make something that sheds light on not only my pain, but the pain that is reflected in millions of Black Americans across the country. That’s what I do.

I try to have conversations with people about my work. It’s a big part of my process. I’m a very process-oriented artist. So when I have a gallery show, I often will take one person, talk to them about each piece individually, and just try to hear their story about their relationship to my work. Because it’s important to me to understand the way people perceive my work in relationship to the way I create it and see how those intentions are aligned or not aligned. One, for me to be more clear, and two, for me to say, “what is your relationship to this Black work?” I am making Black work. Specifically Black work.

I don’t spend a lot of time on social media looking at Black Lives Matter movement material, articles, people’s opinions about it, like on Facebook, just because it can be so inflammatory. And not even uplifting, sometimes it can be like “well this is why this is fucked up.” And I don’t have to read why this is fucked up right now. Because I know that it’s fucked up too. It isn’t encouraging to me. So I’m trying to create an encouraging, inspiring space for myself so I can leave my house every day. Understanding who I am: who I am in relationship to my ancestry, who I am in relationship to this political dialogue that’s happening, who I am in relationship to no one else, just myself. And like, being okay with in my identity so that I can have that voice, to use it to speak out against brutality, to speak out against sexism and homophobia and transphobia and stuff like that.

Jon, do you have anything to add?

Jon: I mean, I guess the way that I cope—I come home days, and I just cry. Some days you just have to do that. Why am I crying? I’m crying because things are overwhelming, things are overbearing, tragedies are happening every day. And then sometimes it’s just having conversations with people about it. People who are down for the cause. Because it’s so difficult to have conversations with people who just don’t get it. Because it’s too painful. It’s too painful and too personal. It’s like, “why don’t you get it? Why don’t you think that this is an issue?”

Jarrett: Which is why art is nice! ‘Cause suddenly I don’t have to have a direct conversation with a person that I don’t think will understand that I’m framing it from my experience, but if I can put this piece of art in front of you, and suddenly you’re dealing with my relationship with this whole thing, but it’s not coming from a Black person’s mouth, you’re just seeing and you’re meant to deal with it, and suddenly you can come up with different conclusions about it, and I can help bring those conclusions by our conversations, that’s way better.

Jon: Which is why to me it was important to use graphic design as a way to talk about this issue. Because graphic design is visual communication. It’s the way that people perceive images. We’re constantly surrounded by images, it’s inevitable. Having images, also to Jarrett’s point, that feel more uplifting, that feel healing for our community, I feel, are also productive ways to cope. I’m one of those masochist people that like to read the comments on articles. It’s a nice reminder that there are people out there in the world that are fucking crazy, and you need to be woke for it. You can’t do it every day, but sometimes I like to do it.

I feel like a lot of my work is trying to engage a sense of hope.

If you could summarize what you think the movement’s goal is right now, what would you say?

Jarrett: I think it’s to force people to pay attention.

Jon: That’s what I was gonna say. It’s more than advocacy, but it’s like advocacy work. And it shouldn’t be advocacy work, but just because of the way that our society is, people don’t even think about it. And it’s clearly protests, people mourning together, or trying to heal together.

Jarrett: But honestly, I don’t think the movement is focused enough on healing. How can we reframe “I can’t breathe” and “hands up don’t shoot” to something more positive and inspiring? I refuse to put the hashtag #Icantbreathe and #handsupdontshoot because it focuses on the act of death, it focuses on the victim, it focuses on the martyr, and it doesn’t focus on the community and the person and the humanity in these people.

Jon: those things are important to rally behind, they are important to have existing. However that’s not the only thing that we can cling to.

Jarrett: And that isn’t gonna be the prose that moves us forward, either.

Jon: Because not only are we still continuing to fight for our innate rights, but I still think that we can’t just hurt ourselves in the process. We can’t continue to cry and mourn and hate ourselves for this. There has to be some point that we take care of each other. Yes, people’s lives are being taken. We have to take care of those people, they have families. They lost someone, yes, they’re mourning, but we have to help them heal. We can’t just be there for when they are mourning.

We can’t continue to cry and mourn and hate ourselves for this. There has to be some point that we take care of each other.

Jarrett: What does this model look like? How do we want our children to talk about race in this country? How do we want this period of time to be framed? ‘Cause if you think about the ‘60s and the ‘70s, you have Black Power, “Black is beautiful,”

Jon: —The Black Panther Movement.

Jarrett: —Yeah, all of that really beautiful advocacy and protest work, and now, our gesture is the surrender sign with two hands up. The language isn’t anything that I want my children to say that I said, honestly. What I would want my children to say I said instead is “I am a man;” “I am;” “Ain’t I a woman;” “Ain’t I.” All these things that—”We are bulletproof”—something that rallies the community, that makes Black people feel empowered, worthy, and we’re not just victims. Because we are more than just victims; we’ve been in this damn country for 400 and some-odd years. We built this country. We’re not fucking victims. We can do this, we just have to be able to encourage and empower ourselves.

How do we want our children to talk about race in this country? How do we want this period of time to be framed?

Jon: Like Viola Davis said when she was accepting her Emmy, it’s all about opportunity. I think that the Black Lives Matter movement is an opportunity for us to make this issue important, to be in spaces that we have never been in; to bring this discussion to people’s dinner tables that don’t even think about it. And even if they don’t agree with the movement, at least they’re talking about it. That’s what I think the biggest thing about the Black Lives Matter movement is: it’s an amazing platform.

How do I live my life without always being angry? How do I live my life without always being scared?

I think there’s still a lot of work to be done. The problem hasn’t been solved, I don’t think we can pack our shit up and go home. I think that it’s doing a lot of work. But I think that there is still healing that has to happen. I think that the Black Lives Matter movement is dealing with a lot of social and larger structural problems, but also we have to deal with personal problems as well. We have to deal with the trauma that comes with it, and healing that trauma. We have to move forward: okay we’re doing this together, we’re solving this problem, but also how do I live my life without always being angry? How do I live my life without always being scared? How do I live my life without always being in fear of everything? I think that is what’s starting to happen. People are making art about it, people are making projects about it, but obviously we’re not done.